How do you recover from a scam? Understanding scams from a Feminist Perspective. Closure of Life After Scams. New Podcasts to listen to about how I experienced the scam and how I recovered.

I often get asked “ How do you (they mean “I”) recover (from a scam)?”

It raises the question, what is meant by ‘recovery’?

Does ‘recovery’ mean:

- Understanding what has happened and why?

- Getting over being ‘in love’ with your scammer?

- Having ‘normal’ relationships again?

- Finding someone in the real world to love or be in relationship with?

- Dealing with the financial devastation?

- Finding a way to live with reduced financial expectations?

- Get lost funds back?

- Returning to normal relationships with friends and family?

- Being able to ‘get on with life’ and trust others and one-self?

- Come out from behind the shame and guilt about one’s part in the scam?

A friend who was experiencing grief over the death of a child said “You don’t get over it, you learn to live with it”. This is very much how I feel about recovering from being caught in a scam. But learning to live with it does not mean in any way being closed off about what has happened. For me, going public about being scammed was the most impactful action about my recovery. It means that I

- Acknowledged that I had made a mistake, and that making mistakes is OK, it is human. I was able to forgive myself for getting caught in a scam, and for being out of rational control while in the scam

- Educated myself about scams, and educated others about scams by writing about this in my blog, and my book, and speaking out publically about my understanding of scams

- Regained my self respect every time I spoke up about being scammed, and was able to overcome being shut down and isolated from the shame of being scammed

- Sought to make a difference to others either to prevent them making the same mistake, or, by sharing my experience and understanding about what people feel after a scam, hoping they feel less alone

- Continually, when interacting with a scam victim, or talking to the public, put the responsibility back onto the perpetrators of scams. Whatever my personal responsibility was it was minimal in the face of the individual fraudulent activity of scammers and organised crime in general.

- Highlight the power imbalance of scammers who train themselves to be skilled emotional manipulators by using proven scripts, lying and cheating without compunction against victims who open themselves to friendship and love from the goodness of their hearts.

Dr Cassandra Cross says, after much research into scams,

“People cope differently from this experience: some are angry, some are depressed, some talk of suicide, while others spend every waking hour trying to figure out how they were scammed and try to prevent it happening to others.”

Cassandra Cross, Lecturer in Criminology at QUT. Love Hurts: the costly reality of online romance fraud. The Conversation. 11 December 2014, .

I know I am the latter, but not everyone is this. Another quote, about grief, from Stephanie Ericsson, but really its about life!

Recovery is about learning how to live again. Which means:

- Owning your feelings

- Forgiving yourself

- Finding understanding and healing where you are intuitively drawn to it

- Living in the moment

- Finding ways to express yourself fully, creatively, and to others

- Not hiding

And all of this takes time. I can say this fully 9 ½ years after being scammed. It is now time to be proud of what I have done.

Feminist Perspective

I mentioned above about the power imbalance in scams.

My understanding of this was greatly enhanced by this recent opinion piece.

This article takes a feminist perspective on scams, because of their greater impact on women. In this country, at least from the statistics, there is not as great a difference in the numbers reporting scams or loosing money from scams as this article claims, however many of the arguments within this paper echo statements I have made myself.

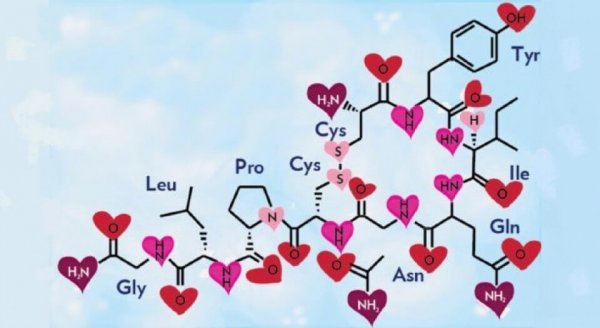

“Love Fraud is a long-con technique that uses social media to find victims and social engineering to subdue them. Scientific research shows romantic love is as addictive as cocaine. Romance scammers leverage this susceptibility through a technique called “love bombing”, using constant, highly validating messaging to trigger an oxytocin dependency in the victim. This grooming process often takes months. Once a victim reaches what scammers refer to as the “ether state”, they’ve essentially been drugged into an emotional stupor that has key psychological side effects including high levels of trust, generosity and impaired judgment with financial decisions. The effect is so powerful that victims — who hail from all education and income levels –are often remotely controlled into draining their bank accounts and sending shocking amounts of their money to someone they’ve never met. Friends and family watch in horror, their interventions powerless over this complex, traumatizing scam.”

Reading this made me remember that after the scam I felt hyper-sexualised, awoken sexually, wanting more sex. Though I have resisted defining the state created in a scam as an addiction, similar to drug addiction, I can see, on reflection, that this hyper-sexualisation is exactly what is being talked about here as the ‘oxytocin dependency’. Maybe I was lucky that I was only in my scam a short time. For those who were in their scam for longer periods, I can understand how it is even harder to step away from the emotional state that is created in a scam. I have seen this often in the victims I have spoken to, and the families that have contacted me about thier loved one caught irritrievably in a scam.

The use of women in particular, to launder money from other scams, often with the witting or unwitting collusion of financial institutions, is definitely worth raising as a feminist issue. Uniting around raising awareness of this would be one way to make the personal become political, and take steps towards recovery from scams.

Life After Scams Closure

Over a year ago I began the process of setting up a new organisation, Life After Scams as a charity to provide emotional help to victims. After a grueling 2020 COVID-19 year, I have found myself with no energy to provide help in this area. I am proclaiming myself and this work done. I am stopping my public work as a scam victim advocate, and closing down the charity.

In the process I have had great acknowlegement about what I have contributed over the past years, and it is now time to claim this. Here’s one…

“Have just seen your email about closing Life After Scams. Sad that this is happening but completely understandable. I just wanted to drop you a note to say thank you for the immense contribution you’ve made to educating people about romance scams and supporting other victims. I am confident that a great deal of heartache and financial pain has been saved thanks to your efforts. I wish you every happiness in the future.

Very best wishes

Delia”

Delia Rickard Deputy Chair Australian Competition & Consumer Commission

Podcasts

Recent publication of two new podcasts end the year 2020 with the focus on scams within the context of relationships. Listening to these highlight how I experienced the scam, how I made sense of it for myself, and how I recovered from being scammed. Many thanks to Georgia Love and Tammi Faraday for these excellent podcasts.

Two new Podcasts published

Everyone Has an EX, Host: Georgia Love

See my Media Page for a full description. Listen to the What’s Mine is Yours episode.

Brave Journeys, with Tammi Faraday

See my Media Page for a full description.

Open the links to get your favourite Podcast provider and listen to Jan Marshall – From Romance Scam Survivor to Warrior episode.

I know from experience that when inside a scam, we are committed to our loved one/scammer, and will do whatever it takes to support or rescue them from the many sorts of trouble they are in. Afterwards we wonder what happened, why we didn’t see what was going on, why we rejected warnings from friends, and stepped over any inconsistencies or red flags that there were. We don’t understand what happened even when looking back on it. Perhaps because the rational part of our brain was dis-engaged at the time. Instead our brain was immersed in the fog of oxytocin. Afterwards we mostly blame ourselves for what happened and loose trust in ourselves. After all, we actively gave the money. Or did we?

I know from experience that when inside a scam, we are committed to our loved one/scammer, and will do whatever it takes to support or rescue them from the many sorts of trouble they are in. Afterwards we wonder what happened, why we didn’t see what was going on, why we rejected warnings from friends, and stepped over any inconsistencies or red flags that there were. We don’t understand what happened even when looking back on it. Perhaps because the rational part of our brain was dis-engaged at the time. Instead our brain was immersed in the fog of oxytocin. Afterwards we mostly blame ourselves for what happened and loose trust in ourselves. After all, we actively gave the money. Or did we?